HISTORY OF HERNANDO COUNTY SCHOOLS

The Ozello School

The Ozello School (Truxal)

The following is excerpted from a 1985

article “Early Schools in Hernando County” by Nellie L. Truxal.

In 1880, the little settlement of Ozello

had a serious problem in locating a school.

Until this time the only school was a tiny

building on a point of land on the bay. A

family had settled there and since there was

no school, the mother collected eight or

ten children and taught them herself. As

other families moved into the area and

settled on both sides of the St. Martin's

River a new school was needed. People on the

south side of the river didn't want the school

located on the north side. People on the north

side didn't want it on the south side.

Finally a compromise was reached. The school

was built on an Indian mound on a small

island in the middle of the river. This was

agreeable because it was said that a child

who could not row a boat by the time he was

six years old was beyond the hope of education.

The peak enrollment at this school was

fifty-two pupils.

After 1887 Ozello was no longer a part

of Hernando County but it is of interest to

note that the school continued to operate

until the mid 1940's. By that time the older

children wanted to attend high school

in Crystal River so all of the pupils were

transported there by bus. A school boat

picked up the children in the morning and took

them to the bus. After school they returned to

Ozello by bus and were taken home by the school boat.

Mr. Robert Wells of Crystal River, who

attended the island school many years ago,

described it as a 24' x 30' building with

a wood burning heater and three hanging coal oil

lamps. There were never any electric lights

in the building. He had very pleasant memories

of the school, except for one man the teacher

who made derogatory remarks about the community

and the way of life there. He was “run off”

by the pupils and replaced by a woman teacher.

Robert Wells remembers the school as being

like a big happy family. He related that

after the school closed it was used as a polling

place for a time. When a storm washed

the building off its blocks it was finally

demolished. The island in the middle of the

river is still known as “School House Island.”

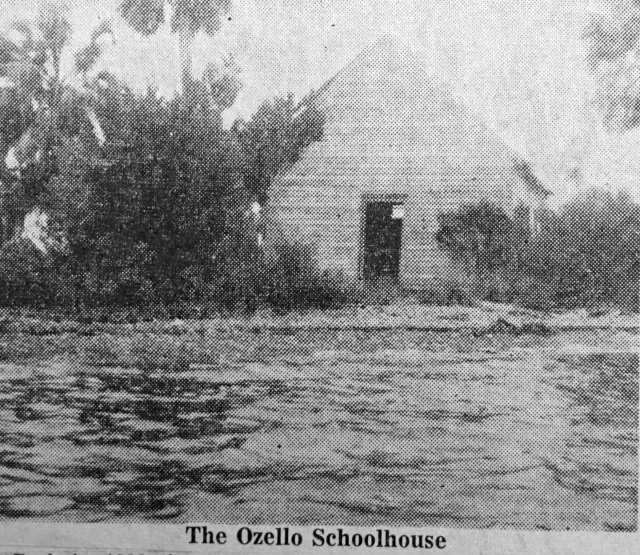

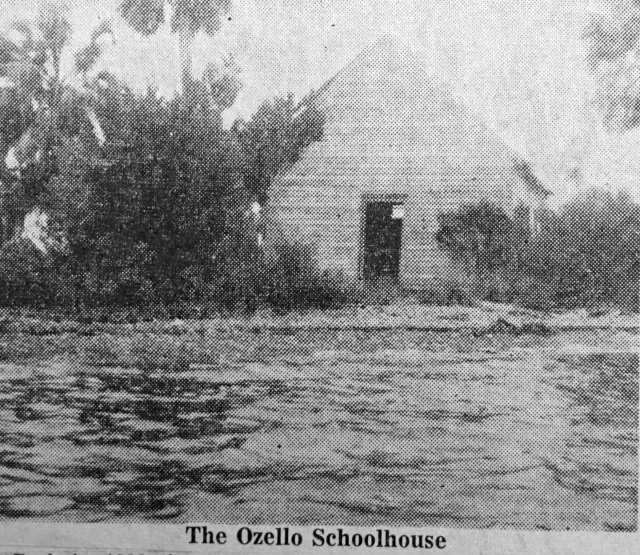

The Ozello School (Dunn)

The following is taken from Back Home: A History of Citrus County, Florida, by Hampton Dunn.

Another landmark went up on the west side of the county in 1880: The neat little schoolhouse

at Ozello, which was to gain world-wide recognition as “The Isle of Knowledge” when noted

cartoonist Robert L. Ripley featured the unique school in his syndicated newspaper feature,

“Believe It or Not!” Mrs. Epie Bullard, went to school there and has researched the history of the

island. She reports the school was built on an island in the center of the St. Martin River because

the people who lived there could not agree to have it built on either side of the river. Finally,

they decided to put in on an island equal distance from each side. Families living in Ozello

were the Heads, Debusks, Stanalands, Stephens, Browns, Martins and Boatrights. Mrs. Bullard

recalled, “The most amazing thing to me at the time was the fact that all the children from first to

eighth grade had to row a boat to school. Needless to say, we had plenty of muscles, blisters, and

worn out seats.” On Sundays, the old school was used as a church, this time with parents using

the boats.

At first, there was a log house with a palm-thatched roof that was used for the school, then

later came a frame structure. It was phased out in 1943. According to Mrs. Cattie P. Martin, a

former teacher at Ozello, the. school reached its peak attendance of 52 pupils back before “The

Freeze” of 1894-95. Other teachers who taught at the Ozello school were Miss Marian King, Miss

Bessie King, Miss Emily Vause, Miss Rosa Hammond, Miss Leila Zeilner, Miss Mamie Love,

Mrs. Jessie Gay Winn, Miss Bessie Martin, David Tyre, Mrs. Cattie Priest, Mrs. Idella Wells,

Miss Sallie Jim Moore, Miss Mary Dell Waring, Miss Sallie Feliston, Alfred O'Steen, Miss Anne

Ashworth, Mrs. Katie Lashley, Dan Rooks, and. Miss Elaine Barnes.

Since 1943, when Mrs. Martin resigned as teacher, the children have been transported by

school boat and bus to Crystal River school. School boats have been used in many Florida

counties since schooling became mandatory in 1939.

Ozello Children Rowed to School;

If Youngster Couldn’t Row Boat He was Beyond Hope of Education

This article appeared in the Tampa Sunday Tribune on Feb. 26, 1956.

The old town of Ozello, Fla., retains its two most distinctive

features. You still have to cross its principal thoroughfare — the

St. Martins river — by boat; and the community schoolhouse, in use

from 1880 until 1943, still stands on a tiny island in midstream.

Ozello and its environs on the Gulf Coast have been populated, though

sparsely, since pirate days; but, due to difficulty of access by land,

until recent years were not even shown on Florida road maps.

Today, however, there is a newly surfaced secondary state highway

turning due west off Route 19, between Homosassa Springs and Crystal

River, dead-ending at Ozello. This black-topped road takes you through

four miles of jungle and then, for the last mile, across a salt marsh

dotted with palm islands.

These islands are largely formed by generations of shucking the

millions of succulent oysters that abound in the numerous salt water

streams that meander through this coastal savanna.

The lonely landscape is only occasionally enlivened by heron or crane

or a roaming herd of cattle. Thus approaching this isolated place on the

Gulf Coast somewhat prepares you for the rugged individuality and

tenacity of the inhabitants, which is traditional.

Ozello once had a post office. That is how it was finally named. The

names suggested were numerous and opinions strong. But postmaster

William H. Pratt settled all argument by sending the entire list of

names submitted to his superiors in Washington, D. C., with this terse

note: “You fellows pick a name. I’ve got to live

here.”

There were some nice groves in the making around Ozello when the Big

Freeze hit them in 1895-96. Unlike most other Florida areas, citrus

growing was abandoned after that. Folks just went back to fishing, their

main livelihood.

The decline of Cedar Key as a shipping point was another blow, but

the more hardy stayed on here.

The unique schoolhouse in Ozello, however, remains today a monument

to how this independent little community compromised one of its most

contest issues.

Back in 1880 the folks living on the north bank of the St. Martins

river wouldn’t agree to its being built on the south bank —

any more than those living on the south shore would stand for its being

erected on the opposite side of the river from them. So a tiny island in

the middle of Ozello’s main street — the St. Martins river

— is the site of the old schoolhouse, where everybody had to row

to get there.

Ten years ago Stephen Trumbull, then a roving reporter for The Miami

Herald, looked up Jim Brown, an old-timer who had moved to Ozello just

as the earlier school was being abandoned and the local youngsters were

beginning to go to the island school.

He said the first school was palmetto-thatched and stood on top of an

Indian mound on the north side of the river. When his son, John, went to

the new school there were 20 pupils attending.

Locating their school on an island was accepted by all, he explained,

because “a youngster who couldn’t row a boat by the time he

reached school age, in those days, was considered beyond all hope of

education.

Then, too, there was a lot of boat-pooling, one family doing the

hauling one week, and another the next.

But some say that’s why they couldn’t get another teacher

after Mrs. Catty Martin got herself a better job teaching in Crystal

River. They couldn’t find another teacher willing to start and end

her day with an uncomfortable boat ride.

Others say that, by 1943, lots of the boys started getting a

hankering for high school and since there had to be a school bus to take

them to Crystal River they decided to take the young ’uns there

too.

Ozello’s isolated little schoolhouse still serves its purpose

as official polling place, though.

There’s been no recent agreement among the 20~odd registered

voters in the precinct on a more reachable place. And, the approach by

water is no hardship for those fishing folk, more accustomed to

traveling by heat than car.

Ozello’s island school had its peak attendance (52 pupils) in

the prosperous days when Cedar Key, to the north was the metropolis of

the West Coast. That was before the Big Freeze when most folks

hereabouts planned to get rich in the citrus business.

There was no paved highway into Ozello in 1946 when Mr. Trumbull

undertook to drive there.

After making the trip he wrote: “The six miles down here from

U. S. 19 may not be the worst road in the world, but it’ runner-up

for that dubious distinction. No cars were passed on the way in or out,

which was fortunate. It’s a one-way, one-land affair, starting in

the cabbage palms and ending on a salt marsh. John Brown says the duck

hunting and fishing is so good that a lot of people brave that road, but

it’s a well known fact that duck hunting and sports fishermen are

nearly as crazy as roving newspaper correspondents.”

By 1954 the state road department had widened and surfaced the road to

the banks of the St. Martins River; and, recognizing the natural

attractions for sportsmen and tourists, erected a wayside picnic area

alongside the new highway.

Ozello began to be shown on the latest road maps and The Miami Herald

sent a staff writer, Bob Preston, to do another feature picture-story on

it. Free of the road hazards Trumbull described, he found: “The

newly surfaced secondary state highway connecting Ozello with the

outside world provides five miles of the most picturesque scenery of any

highway in Florida.”

On arrival, however, all he could see of the community was two

houses, the school and a fishing pier. The homes of the other five

families then living there faced either bank of the river. No store,

street lights—or municipal government—disturbed the peaceful

surroundings yet. There was evidently more river than road traffic

locally.

Noticing a new truck among the boats in the front yards of one of the

two houses near the new road, Mr. Preston approached and discovered the

younger Mr. and Mrs. John Brown and their two little boys, Jim and

Thomas, live there.

John Brown, constable of the district, declares this is just a title.

Nobody gets in serious trouble in Ozello. The natives, unaffected by the

civilization to their east, are attuned to the great silence of nature

in their watery wilderness.

But some, like himself, had bought better cars or trucks with a

modern road connecting them with the outside world. And most expect a

local boom because of the exceptionally good fishing and hunting there.

While Ozello children now commute by bus to school in Crystal River,

the majority still begin and end the journey by water. School bus driver

James Stephens starts his morning trip by boat from his riverbank home

and picks up most of the children in his boat before reaching the bus

parked where the new road begins in Ozello. The old schoolhouse here is

still official voting place for the precinct.

This winter Mrs. John Branch revisited Ozello, having spent several

years of her early youth in the vicinity. She borrowed John Brown

Sr.’s copies of the several clippings from The Miami Herald quoted

above and kindly forwarded them for appropriate use on this Pioneer

Florida page.

Persistent rumors of buried treasure near Ozello recall the earlier

history of this remote stretch of the Gulf Coast in Citrus County, when

pirates frequented the shores. The remains of a huge Indian mound in

Ozello prove more ancient habitation of this waterfront. And there are

ruins where big salt kettles were operated only a few miles away on the

Salt river during the Civil War—though these are almost concealed

by dense woodland now.

Mr. and Mrs. M. Coate of Floral City and others interested in preserving the colorful

history of Citrus County have indicated they would make generous contributions

to establish a museum. The organization of a county historical commission,

as provided by law in Florida now, would be the logical first step towards this end.

We hope the old island school in Ozello will be considered as a most appropriate

site for a local museum there.

|